A mix of compelling ideals and concepts from a variety of disciplines

drive the project. Here's an overview:

The Zombie Effect

The Village Well

The Third Place

Beyond the technologists

Beyond

tasks and "users" Seeds

before trees

Build along

the path

First, do no harm

Build from what exists

THE ZOMBIE EFFECT

Zombies in horror movies walk and talk, but they're

no longer human. A zombie's mind and soul and spirit are gone.

THE ZOMBIE EFFECT

Zombies in horror movies walk and talk, but they're

no longer human. A zombie's mind and soul and spirit are gone.

Many complain that electronic devices -- mobile phones, laptops, headphones and televisions, in particular -- brings with them what we call the "zombie effect." Sometimes people look like zombies when they use such devices, as they focus on faraway people and events and information. In doing so, they devote less attention to the people and places and activities nearby. Onlookers experience an odd feeling as they look around at the disengaged people who "aren't all here."

We've heard a lot of concern about this from café owners, patrons and staff. We've heard many references to the cold, quiet ambience that can infect a place that was once full of warm, friendly face-to-face conversation but is now pervaded by blank-eyed "zombies," faces bathed in laptop glow as they tune out the people around them to focus on faraway Internet activities, or as they concentrate on mobile phone conversations with distant friends and colleagues. The Zombie Effect can insulate people from serendipity, from the possibilities of new friendships and fruitful interactions with the people around them. Like urban sprawl, it can also wash away regional flavor and the sense of place. But through thoughtful design, we can enjoy high tech while minimizing and counteracting the Zombie Effect.

THE

VILLAGE WELL - For thousands of years, water was a resource that

strengthened local human community -- the village well was a place that

people had to visit each day to gather water. In coming to the well, different

people met one another and conversed, enjoying a powerful secondary social

benefit in addition to the well's primary benefit (water). A new technology

(cheap and widespread plumbing) emerged to remove the biological necessity

of visiting the well. Now, in many parts of the world, the institution

of the village well has disappeared, and so have its secondary benefits.

THE

VILLAGE WELL - For thousands of years, water was a resource that

strengthened local human community -- the village well was a place that

people had to visit each day to gather water. In coming to the well, different

people met one another and conversed, enjoying a powerful secondary social

benefit in addition to the well's primary benefit (water). A new technology

(cheap and widespread plumbing) emerged to remove the biological necessity

of visiting the well. Now, in many parts of the world, the institution

of the village well has disappeared, and so have its secondary benefits.

In certain ways, today's wireless Internet cafés resemble

village wells -- they're places that a lot of people visit, many

on a regular basis, to gather a resource. In this case the resource isn't

water, it's bandwidth. In some cities in North America, these little bandwidth

wells are springing up in almost every neighborhood.

But here's a key difference: the filling of containers

at the village well allowed people to observe one another and converse.

The use of bandwidth in a wi-fi café can, and often does, discourage

public observation and conversation in that place.

Many of the people we've interviewed who own or work in cafés,

and many café patrons, have complained of the "zombie effect"

described above. This is ironic because information technology can be

very good at enabling people to meet and communicate across great distances.

Can't it also be used to bring together the people in the neighborhood?

If it can, we wouldn't know, because most of these technologies -- especially

wi-fi -- have been presented to people as mainly a tool for long-distance

communication. Perhaps we can help local communities make great strides

in this direction by simply allowing the technology to be used in the

way village wells were used.

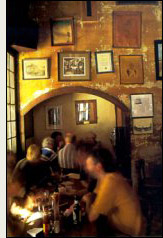

THE

THIRD PLACE- In The Great Good Place [see related

work], Ray Oldenburg described "third places" (or "great

good places") as semi-public hangouts that people visit voluntarily,

unlike the “first” and “second” places of the

home and the office, where people must go to fulfill the requirements

of family and work. Classic examples of these "great good places"

include the traditional Irish pub and the Viennese café . In such

places, people in the neighborhood meet one another, chat and exchange

information and develop friendships. Oldenburg describes such places as

relaxed, informal and inexpensive. Here people can set aside the concerns

of home and work temporarily and gather simply for good company and lively

conversation.

THE

THIRD PLACE- In The Great Good Place [see related

work], Ray Oldenburg described "third places" (or "great

good places") as semi-public hangouts that people visit voluntarily,

unlike the “first” and “second” places of the

home and the office, where people must go to fulfill the requirements

of family and work. Classic examples of these "great good places"

include the traditional Irish pub and the Viennese café . In such

places, people in the neighborhood meet one another, chat and exchange

information and develop friendships. Oldenburg describes such places as

relaxed, informal and inexpensive. Here people can set aside the concerns

of home and work temporarily and gather simply for good company and lively

conversation.

Third places nourish community not only through maintenance of ongoing close relationships, but also through the development of new acquaintances and interactions with a wide variety of people beyond one's narrower social circles defined by work, class and profession. In a healthy third place, Oldenburg says, the stranger feels at home, and is often engaged in easy conversation with the regulars. Oldenburg argues that the casual, comfortable, democratic mixing of people of different ages and classes and types in the Third Place forms the heart of healthy urban communities. The Third Place brings about "the kinds of relationships and the diversity of human contact that are the essence of the city," Oldenburg wrote. The sorts of personal information exchanges that happen in Third Places have historically played key roles in the development of political movements including the American Revolution, whose seeds were sown in colonial taverns, and the sorts of social activity that takes place in the Third Place is "essential to the political processes of democracy," Oldenburg wrote.

How does high technology fit in? Oldenburg writes that, in the absence of healthy Third Places, "the only predictable consequence of technological advancement is that [people] will grow ever more apart from one another." But can we use new technologies to revive our culture's lost third places -- or to invent new sorts of third places?

Does the introduction of high tech into real-world spaces inevitably lead to the Zombie Effect -- do laptops, mobile phones and the like somehow weaken localized face-to-face interaction (and the serendipity and diversity that comes with such interaction)? Let's hope not, because digital technology is pervading our surroundings at a breathtaking pace, in the form of portable devices (mobile phones, PDA's) as well as input devices (sensors, controls) and output devices (displays, speakers, etc.) being embedded in the places where we dwell.

Is the Zombie Effect just a result of artificial constraints built into the technology by technologists? What if we simply let people use their mobile devices to interact with others nearby? What if we expanded the narrow design of these devices to support and enhance the place-based group interactions that people have engaged in naturally for thousands of years?

We hope, through thoughtful design, through the collaboration of leaders from multiple disciplines, and through the active involvement of everyday people, to steer the development of stronger, digitally-enhanced Third Places that will fortify the sense of place and rejuvenate local communities in our 21st Century cities.

BEYOND THE TECHNOLOGISTS - This sort of thoughtful design depends on deeper perspective than traditional software design paradigms can provide. It requires design knowledge, and entire ways of seeing, that have been developed over hundreds of years by people who design places and communities: architects and urban planners. More importantly, such design requires active participation by the people who will use and be affected by the technology.

A keystone of our design approach is the fact that technologists don't create new technologies on their own. New technologies evolve through an interconnected series of activities involving the people who use the tools (individual users as well as groups and communities) and the technologists (engineers, designers and businesspeople). Urban planners are keenly aware that the creation of a successful street or park or café depends much more on the involvement of the surrounding community than it does on the work of the planner or the city government or of local businesses on their own. But this is a point that too many people in the information technology industries are habitually blind to. The history of technology shows us again and again that new technologies are never born fully formed -- the first version of a new technology often barely resembles a mature version of that technology. An invention needs to be used, absorbed and reshaped before it can reach its full potential. Technologists alone can't predict how a new technology will be used.

BEYOND

TASKS AND "USERS" - Traditional task-centered and user-centered

analysis and design methodologies have limited use in this space

-- in fact, they might be counterproductive if misused. Here are three reasons for

this:

BEYOND

TASKS AND "USERS" - Traditional task-centered and user-centered

analysis and design methodologies have limited use in this space

-- in fact, they might be counterproductive if misused. Here are three reasons for

this:

1. User-centered design is inappropriate on its own, because we're not just dealing with individual users working with individual computers. We're dealing with places where people interact with one another, as groups and as individuals. Computers might mediate or hinder or enhance some of that activity, but computers are secondary to the activity. A focus on user-centered design offers advantages if you're building a game of solitaire or a word processor, assuming that each "user" will always use your creation in a room by herself, devoting all of her attention to her PC, conveniently cut off from any other people, activities or concerns. As computation moves beyond the desktop and the cubicle, however, we can't fall back on such assumptions. We must look beyond this model of a single user staring at a single computer screen.

2. Task-centered approaches don't work here, just as they don't work in designing video games, because users don't come to PlaceSite to carry out a predefined chore. Task-centered design techniques can be fantastically useful for certain purposes. For example, these techniques can be great for optimizing the efficiency of an operator who takes telephone orders for a catalog clothing retailer -- with task-centered design we can build a useful data-entry system tailored to that task of taking orders. Telephones and catalogs have been around a long time, so we know specifically what the operator needs to do. We can learn a lot about how operators do these things now by obeserving them and interviewing them. But we can't predict what people will do with systems like PlaceSite. We won't assume that people will come to PlaceSite to perform a narrow and predictable set of repetitive tasks. We certainly won't pretend that people will come to PlaceSite exclusively to perform workplace-related chores (and the workplace is the focus of most task-centered design literature). Such assumptions would be ridiculous and might be disastrous.

3. Users can't predict how they will use new technologies. Before introducing any form of PlaceSite, we surveyed and interviewed hundreds of wi-fi café patrons and staff in Seattle and San Francisco. We asked about their use of wireless Internet access, and we asked whether they would be interested in using wi-fi to share personal information with other people who are physically nearby, among other things. We were surprised at the positive responses we received, but we can't take these results too far. We assume that what people will actually do with a system like PlaceSite after several weeks of exposure to it, will differ dramatically from what the same people will say if asked what they might do with PlaceSite before they've ever seen the system. It would be a mistake to approach the design of PlaceSite the way we have approached the design of standard Web sites, which people are already familiar with using.

We desperately need new design methodologies to apply to computation beyond the desktop. We have agreed upon a few core design approaches that we hope will point us towards solutions to these problems.

"That which is overdesigned, too highly specific, anticipates outcome;

the anticipation of outcome guarantees, if not failure, the absence of grace."

We recognize that we can't predict how place-based digital communication technologies like PlaceSite will evolve and how they'll eventually be used. We understand that technologists' design decisions can severely limit the uses of technology. So we aim to minimize such self-imposed limitations.

That means: start with a minimalist design, the germ of an idea, a seed that carries with it a new way to use wi-fi and an expansion of what wi-fi is.

Release the seed with little embellishment, keep it simple and rich, with just a few core features. Watch what happens, see how people respond to the seed, see what they do with it. Let them embellish it with their own activity. Iteratively shape the system, redesigning based on people's activity, working with the café patrons, staff and the community to evolve the technology and its uses. Help the seed grow naturally; don't try to build a tree from the top down.

BUILD

ALONG THE PATH, and provide visibility and access from the path - Architects

and urban planners (see Alexander, Jacobs, Whyte in related

work) learn that most successful public squares, parks, and Third

Places share these attributes. By "the path" we mean busy pathways

that many people traverse on a daily basis to complete necessary journeys,

such as those between home and work. Public and semipublic places that

are readily visible from the path, and that are clearly open and easily

accessible to people on the path, might be passed and barely noticed dozens

of times by a busy person. But from time to time that person might have

a few minutes to spare and decide to look more closely at the place, perhaps

to come in for a visit. People attract people, so this checking-out activity

in the place draws more attention from passersby, some of whom come in,

creating more activity in the place. All other things being equal, squares

and cafés with open, gradual, transparent transitions to the outside

(think of an airy café with tables and umbrellas spilling out onto

the sidewalk) are more successful than such places that are handicapped

by closed, dramatic, opaque barriers between outside and inside.

BUILD

ALONG THE PATH, and provide visibility and access from the path - Architects

and urban planners (see Alexander, Jacobs, Whyte in related

work) learn that most successful public squares, parks, and Third

Places share these attributes. By "the path" we mean busy pathways

that many people traverse on a daily basis to complete necessary journeys,

such as those between home and work. Public and semipublic places that

are readily visible from the path, and that are clearly open and easily

accessible to people on the path, might be passed and barely noticed dozens

of times by a busy person. But from time to time that person might have

a few minutes to spare and decide to look more closely at the place, perhaps

to come in for a visit. People attract people, so this checking-out activity

in the place draws more attention from passersby, some of whom come in,

creating more activity in the place. All other things being equal, squares

and cafés with open, gradual, transparent transitions to the outside

(think of an airy café with tables and umbrellas spilling out onto

the sidewalk) are more successful than such places that are handicapped

by closed, dramatic, opaque barriers between outside and inside.

We see PlaceSite as analogous to a public place built along a busy path.

The busy path here is not a physical one; it's the path between a specific

wi-fi café and the virtual placelessness of the Internet, which

many laptop-toting café patrons follow each day. PlaceSite technology

appears to everyone who takes that path, and the activity of people using

PlaceSite is visible at a glance to everyone else passing by. To what

extent will the attributes of successful physical public places carry

over to hybrid physical/virtual public spaces? We hope the response to

PlaceSite will begin to answer this question.

FIRST, DO NO HARM - As computation moves beyond the desktop, following us wherever we go, people can no longer escape software and problems that come with it by just turning off our computers or walking away from their desks. Ethical concerns are more important than ever as we design such software, and the PlaceSite team approaches every aspect of the project with a philosophy of "first, do no harm." For example, we design for incremental revelation of all personal information. This means we default to a state of no personal information being shared -- a user must explicitly choose to share any such information before it will appear on the system.

BUILD FROM WHAT ALREADY EXISTS - We're trying to help ubiquitous computing evolve from today’s places, communities and technological infrastructure. Wherever possible we avoid imposing new behaviors, tasks, hassles, and expenses on the people who use the system, and we stay out of the way of café staff and people in the surrounding neighborhoods. Development of any new technology involves change. But we strive to provide core benefits using what's already in place where possible, respecting the context of the local community we're serving and enhancing that context. An important example: we don't ask café patrons to install any new software in order to use the system -- once PlaceSite is in place in a café, a café patron can immediately enjoy all benefits of the system via the Web browser that she already uses.

We're also tremendous fans of the open source software movement. We've used open source software wherever we can as building blocks on which we constructed the online portion of the project, and we will share software that we build with the open source community, to spur further development and improvement of PlaceSite and similar place-based community-building projects.